Developing effective approaches for teaching QI principles and methodology can be challenging. It is further complicated by the lack of consensus around the definition of quality and how QI differs from research. While both research and QI are essential to ensuring high-quality health care, there are several distinct features of QI that must be recognized and defined.

QI vs Research: What’s the Difference?

Simply stated, QI involves improving processes of care, while research seeks to improve clinical evidence. The main goals of health services research (HSR) are to identify the most effective ways to organize, manage, finance, and deliver high-quality care, reduce medical errors, and improve patient safety. Similarly, outcomes research seeks to understand the factors in health care delivery that are primarily responsible for differential results, such as mortality or quality of life.7

HSR and outcomes research share features common to all research: biases are carefully controlled for using randomization, unequivocal outcomes are measured and significance thresholds are set, classic biostatistics are utilized to analyze data at the end of the project, and the work is powered to definitively answer a question. QI, on the other hand, seeks to operationalize best practices with a series of small changes. Data need only be sufficient to meet confidence thresholds for action or decision, are analyzed in real-time, and trends influence next steps (Table 1).

Table 1. The differences between research and quality improvement

In order to design effective QI interventions, surgeons must be knowledgeable about the factors that influence the outcome of interest—the HSR and outcomes literature. QI interventions are based on knowledge generated from research, but the process of QI does not itself follow the tenets of research. Practice guidelines and standards derived from research often take years to reach implementation, while QI efforts are held to a more immediate and actionable time frame. For QI interventions to be successful, surgeons must also understand and apply principles of change management and team leadership. Change management is the science of preparing and supporting individuals and teams in the face of implementing new concepts, programs, and routines. Understanding these differences is a critical first step to help surgical educators set expectations for resident-led QI projects.

Barriers to Resident Engagement

Engaging residents in meaningful QI efforts is a significant challenge for surgical educators. Residents across specialties have struggled with overload and the challenge of adding yet another component to their curriculum, as well as lack of a shared vision for how to conduct QI and poor clarity of curricular content.8 Residents have expressed frustration with contributing to improving local health care systems without feeling that their efforts are acknowledged or valued. Educators must address these barriers if QI curricula are to be successful.

The conditions and contexts for learning are critical to the development and outcomes of QI curricula, as QI efforts occur within the clinical setting of increasingly complex health care systems. Conditions for learning include the content of the curriculum, instructional methods, learning sites, faculty, time, facilities, and health care teams and systems. Contexts for learning include faculty role-modeling, institutional values, culture and politics, and socio-political-economic forces.9 The six tips that follow incorporate and address issues within this framework.

Establish a Formal Curriculum

While we acknowledge that many programs struggle with limited resources to expand existing curricula, the importance of establishing a complete curriculum, including goals, objectives, and assessment of learning outcomes, cannot be overstated. Residents across specialties have expressed confusion about what is being taught, what is expected of them for participation and outcomes, and the purpose of learning QI.8 Providing clarity through a comprehensive curriculum is the first step to addressing these barriers. We have found that formalizing a program for learning QI skills helps to mitigate the sense that QI projects are simply checking a box. Rather, residents should know that they are learning a valuable skill set that they will use in their future practice. Additionally, our experience suggests residents are more likely to view QI curricula positively and engage in the when institutional and departmental leadership, program directors and other faculty show explicit support. The American College of Surgeons Quality in Training Initiative Primer is an excellent curricular resource that can be readily implemented within surgical residency programs.10

Optimize Instructional Methods

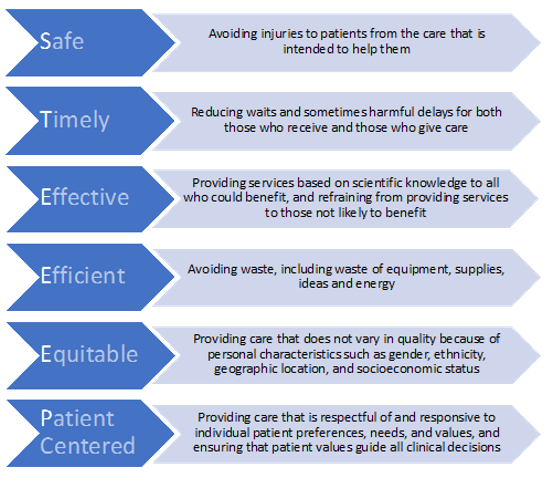

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) Open School online modules are a popular instructional method to deliver core content on QI to residents11; however, for curricula on QI principles and their application to be effective, instructional methods must go beyond online modules. Experts in medical education and adult learning principles have suggested that a combination of didactic and experiential learning is the optimal approach to effective instruction in QI.12 The didactic component of the curriculum should provide clarity on the concept of quality, identify differences between QI and research, and outline practical steps for leading QI initiatives. Online modules are excellent resources to deliver content, however, in-person discussions are critical to ensuring improved quality and safety are adopted as lifelong goals, rather than just a box to be checked.

Once residents haven a proven understanding of the QI curriculum, they must “show how,” by demonstrating knowledge and competence in practice by leading QI projects.13 In our experience, the primary focus of QI project involvement should be learning and practicing the principles, not project outcomes. QI work is messy and fraught with barriers and challenges, many of which are out of the control of the average resident. Therefore, understanding fundamental QI principles with ongoing engagement in QI should be the goal.

Address Institutional Culture and Values

Management guru, Peter Drucker, is attributed as saying, “culture eats strategy for breakfast.” This is as true in establishing effective QI curricula as in the business sector. The most well-considered QI curriculum will miss the mark if institutional culture surrounding QI is not identified and addressed. The values of the institution influence residents’ ability to implement change through QI processes. Furthermore, Adult Learning Theory posits that residents will learn best when they see a need to acquire knowledge and skills in a particular domain.14 This suggests that residents are unlikely to develop an intrinsic motivation to learn and apply QI skills without appropriate faculty role modeling of its importance. Changes in culture come from the top and it is critical to engage high level stakeholders when implementing a QI program. By engaging senior leadership first, the culture of quality will permeate all aspects of resident training, not just the siloed QI curriculum.

Support Faculty QI Champions

Our current trainees are faced with mandates to learn something for which there are exceedingly few teachers and even fewer experts.15 For any QI curricula to succeed, faculty development is critical. (See Appendix for opportunities for advanced training in quality improvement and patient safety.) Residents should have the opportunity to interact with a faculty champion or curriculum director as they learn foundational principles, as well as a faculty coach or mentor as they work through a QI project. Educational leaders in QI have suggested that resident projects fail for two reasons: (1) burnout of the few faculty who are qualified to coach projects, and (2) lack of faculty engagement to ensure QI project success.16 Interested faculty should be identified and encouraged to obtain training in QI through a variety of certificate programs that are now available institutionally and nationally.16–19 Finally, QI principles are universal across specialties and health care professions, so seeking teachers and coaches outside of the department of surgery is an important avenue to consider.

Integrate and Align with the Hospital System

Hospital operations and graduate medical education (GME) alignment need to be addressed to support QI curriculum development and implementation. Implementation of effective QI curricula requires access to infrastructure and resources such as data, project management, IT support, and process improvement expertise, which are likely to reside within clinical operations. A QI initiative is more likely to gain access to these resources if it falls in line with the hospital’s strategic priorities, particularly if the resident is able to present a business case that estimates savings for the institution. However, GME and clinical operations leadership and their missions typically exist in silos and are not routinely aligned. In order to improve alignment, residents are encouraged to develop relationships with hospital quality leaders. GME-wide house staff councils are one way to facilitate this.20 Appointing resident representatives to institutional QI councils and committees can also improve communication and collaboration between residents and hospital leaders.21 Projects that are derived from partnership with the hospital are also more likely to affect day-to-day experience of those involved and can increase engagement of residents and faculty who are able to see the problem and results of their efforts in real time.

Celebrate Successes and Make QI Efforts Visible

Celebrating resident QI efforts is critical to achieve buy-in from the residents and promote success of the QI curriculum. Residents should be given the opportunity to share their work at conferences, such as grand rounds.22 The University of Utah has established an annual Department Value Symposium where residents present abstracts of their QI work and a keynote speaker is invited, similar to resident research days that are commonplace across programs. Furthermore, QI is not unique to surgery and engagement with other specialties, as well as administration, can be leveraged to establish QI symposia or learning days outside the department of surgery. In addition to demonstrating appreciation for the residents’ work, this serves as an opportunity for faculty development.

Residents should present successful projects directly to the administration. These presentations will expand QI discussion, improve patient care, and show residents their research is valued. Previous work in medical fields suggests that residents may view QI as a lot of extra work, and we must remember to recognize and applaud their efforts.8 Encourage residents to present their work at local and national meetings. As the field of patient safety and QI grows, there is great room for scholarship in this realm. Presenting at QI meetings should be encouraged and valued in line with support of research presentations and conference attendance.

Continuous improvement in the quality of care we deliver can only be achieved by continuous, frontline efforts. Effective QI curricula in residency will empower surgeons to participate in QI efforts in their clinical practice. Taking a cue from the business world on total quality management—a program aimed at increasing quality and productivity—we must “institute a vigorous program of education” and realize that quality transformation is everyone’s work.23