Abstract

Background

A male patient presented it severe acute pancreatitis and abdominal compartment syndrome.

Summary

Our patient is a 54-year-old male who presented with acute severe necrotizing pancreatitis. He was intubated for rapidly progressive respiratory failure and despite ongoing resuscitation developed circulatory failure requiring three vasopressors, acute kidney injury, and abdominal compartment syndrome. He was taken to the operating room and a standard peritoneal dialysis catheter was placed. He received DPR with 2.5 percent Deflex; 1 liter infusion with a 1 hour dwell time every 4 hours. Over the next three days, he gradually improved with decreasing bladder pressures, improved urine output and cessation of vasoactive support, without needing a laparotomy. He was discharged to a rehabilitation center without permanent organ failure.

Conclusion

Due to need for aggressive fluid resuscitation in SAP there is an increased risk for IAH and ACS. Patients failing medical management require decompressive laparotomy with significant morbidity and mortality. As an adjunct, DPR may be able to decrease abdominal pressure and decrease the need for decompressive laparotomy in the setting of SAP.

Key Words

Necrotizing pancreatitis, direct peritoneal resuscitation, abdominal compartment syndrome

Case Description

Intra-abdominal hypertension (IAH) complicates up to 60 percent of patients with severe acute pancreatitis (SAP)1 and Abdominal Compartment Syndrome (ACS) complicates 30 percent.2 Mortality rates of this population are as high as 75 percent.1,2 Direct peritoneal resuscitation (DPR) has been described as a resuscitation adjunct for hemorrhagic shock, and abdominal sepsis. This adjunct has shown improved hemodynamic stability, reduced acid-base imbalance, anti-fluid sequestration and immunomodulatory effects in septic shock.3,4 In hemorrhagic shock, resuscitation-mediated intestinal vasoconstriction and hypoperfusion can be reversed by DPR.5,6 DPR, as an adjunct to conventional resuscitation, has been shown to have multiple effects, including: microvascular vasodilation, increased visceral and hepatic blood flow, reversal of endothelial cell dysfunction, downregulation of the inflammatory response, decreased bowel edema and normalization of systemic water compartments.3,5-7 It has also been shown to shorten time to definitive fascial closure in after damage control surgery with temporary abdominal closure.8 DPR has been shown to be useful in various intraabdominal emergencies, mostly in perforated viscous, small bowel obstruction, and intestinal ischemia, with limited descriptions of use in necrotizing pancreatitis, anastomotic leak, dehiscence and abdominal compartment syndrome.9

Acute pancreatitis is a common disease encountered by surgeons, with many cases being a mild self-limited inflammatory condition. However, in severe cases it can present with hypotension, organ dysfunction, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and death.10 In addition to clinical symptomatology, acute pancreatitis can be further graded based on the CT Severity Index (CTSI). The CTSI is a sum of the Bathazar score, as well as the grading and extent of pancreatic necrosis (both derived from imaging). Treatment and prognosis is based on the sum of values, with 0–3 correlating to mild acute pancreatitis, 4–6 correlating to moderate acute pancreatitis, and 7–10 correlating with severe acute pancreatitis. A combination of clinical symptomatology as well as imaging can help guide initial admission and therapeutic interventions.

In severe acute pancreatitis, severe inflammation leads to further fluid sequestration and more aggressive fluid resuscitation is required. This potential requirement for massive fluid resuscitation presents a major concern for IAH and ACS. Surgical decompression for ACS has morbidity of its own including enterocutaneous fistulas, hernias, and infectious complications.8 Thus, appropriate fluid resuscitation while attempting to prevent ACS, requiring decompression, can be a difficult double-edged sword for the acute care surgeon.

With limited case-specific data for DPR in pancreatitis, we present a case report of severe acute pancreatitis (SAP) with ACS treated with DPR, from our institution. We undertook aggressive supportive measures, with standard intensive care monitoring to test a hypothesis that DPR would reduce intravenous fluid resuscitation, resulting in less abdominal and retroperitoneal edema and avoiding a decompressive laparotomy for ACS in a patient with SAP.

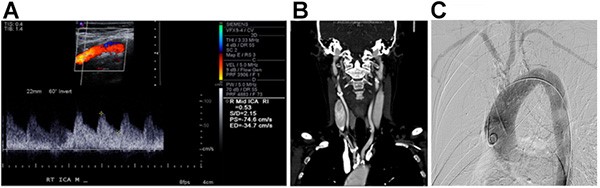

A 54-year-old white male initially presented to an outside institution with acute necrotizing alcoholic pancreatitis and multisystem organ failure. He was transferred from an outside facility to University of Maryland, intubated for respiratory failure, hypotensive, requiring vasopressor therapy, and with concurrent acute kidney injury. Abdominal CT scan was used to further characterize his necrotizing pancreatitis. His CTSI was 9, consistent with severe acute pancreatitis. His initial bladder pressure on presentation to our SICU was 22mmHg. On physical exam patient had significant abdominal distention. He was taken to the operating room for peritoneal dialysis catheter placement.

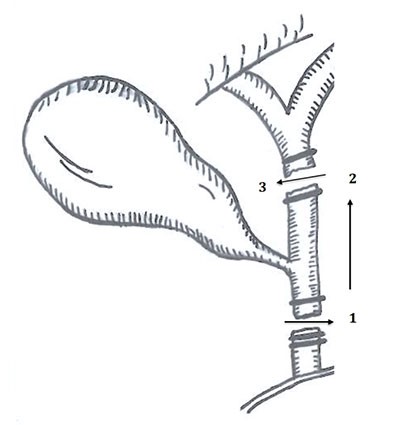

In the operating room a small, lower midline vertical incision for the dialysis catheter was placed. Two liters of ascites was drained from the abdomen and cultures were obtained, that were negative. A standard, tunneled peritoneal dialysis catheter was then placed. DPR then commenced in the ICU with 2.5 percent Deflex solution with 1 liter infusion and 1 hour dwell time every 4 hours. Peritoneal dialysis continued for 72 hours and then it was discontinued. Bladder pressures were monitored every four hours, urine output monitored, hourly, and hemodynamics were monitored as signs of clinical improvement. Ventilator strategies and other critical care followed the standard of care.

On hospital day 1, the patient’s bladder pressures were noted to be elevated at 25 mmHg. He was oliguric with urine output of 505 mL/d. He remained on three vasopressors for hemodynamic support. On day 2, we saw decreasing bladder pressures to 16 mmHg with marked improvement of urine output 1700 ml/d. At this time, the patient was also weaned to one vasopressor. By day 3, his bladder pressure further decreased to 13 mmHg with urine output improved to 2735 mL/d and the patient was entirely off vasopressors.

His PD catheter was removed at this index hospitalization. Due to his systemic illness, he was unable to be weaned from the ventilator in a timely fashion. He did require a tracheostomy and he was successfully weaned from ventilator support. He was discharged on day 29 to a rehabilitation center on trach collar.

Discussion

Patients with necrotizing severe pancreatitis often require significant fluid resuscitation, similar to those with hemorrhagic shock and sepsis, which can lead to IAH and ACS. Placing standard peritoneal dialysis catheters, and initiating DPR in select patients could lead to conservative management and decrease need for surgical decompression, as noted in our patient.

The major limitation of this strategy is identifying patients early enough in their disease process for DPR to be efficacious. A confounding factor in our patient was his 2L of ascites that was drained. Abdominal fluid drainage, whether open or percutaneous is a described treatment strategy for patients with IAH/ACS. We believe that this decompression, as well as the decision to institute DPR, limited his requirement for intravenous fluid resuscitation and prevented the patient from worsening ACS and requiring a surgical decompression with a potential open abdomen and temporary closure.

While Smith et al9 described DPR in patients with many abdominal catastrophes, a majority had perforated viscous, small bowel obstruction or intestinal ischemia (36/48). Only a limited number had other indications, such as pancreatitis, dehiscence, evisceration, anastomotic leak, and abdominal compartment syndrome. All of the patient’s in that study required a laparotomy and DPR was added as an adjunctive therapy. Our case described detailed results in severe acute pancreatitis, using DPR to avoid laparotomy, while achieving improved hemodynamics and resolution of end organ dysfunction.

We propose considering direct peritoneal resuscitation in select patients with necrotizing pancreatitis and IAH or with ACS as an adjunctive therapy that may lead to a reduction in decompressive laparotomy and their complications. Close monitoring and physician judgment is critical to decide whether to continue with the therapy or to abandon the therapy for decompression depending on the progression of the patient. These decisions and findings would best be confirmed with a protocolized approach and a larger prospective study.

Conclusion

Direct Peritoneal Resuscitation, as an adjunct to conventional intravenous resuscitation, may have a selective role in severe necrotizing pancreatitis to reduce edema, increase visceral perfusion and improve hemodynamic stability and decrease the need for decompressive laparotomy due to IAH and ACS. This resuscitation method can potentially lead to improved organ function and improved patient outcomes.

Lessons Learned

DPR can be used as an adjunct to resuscitation to decrease the need for decompressive laparotomy due to IAH and ACS in select patients with necrotizing pancreatitis.

Authors

AP Pasley, DO

University of Maryland Medical Center

Acute Care and Emergency Surgery

Department of Surgery

Baltimore, MD 21201

N Hansraj, MD

University of Maryland Medical Center

Acute Care and Emergency Surgery

Department of Surgery

Baltimore, MD 21201

F Boulos, MD

University of Maryland Medical Center

Acute Care and Emergency Surgery

Department of Surgery

Baltimore, MD 21201

L O'Meara, CRNP

University of Maryland Medical Center

Acute Care and Emergency Surgery

Department of Surgery

Baltimore, MD 21201

R Tesoriero, MD

University of Maryland Medical Center

Acute Care and Emergency Surgery

Department of Surgery

Baltimore, MD 21201

JJ Diaz, MD

University of Maryland Medical Center

Acute Care and Emergency Surgery

Department of Surgery

Baltimore, MD 21201

JD Pasley, DO

University of Maryland Medical Center

Acute Care and Emergency Surgery

Department of Surgery

Baltimore, MD 21201

Correspondence

Dr. Amelia Pasley

Acute Care and Emergency Surgery

Department of Surgery

22 S. Greene St., Baltimore, MD 21201

Phone: 248-892-2250

E-mail: Amelia.fiore@gmail.com

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Al-Bahrani AZ, Abid GH, Holt A, et al. Clinical relevance of intra-abdominal hypertension in patients with severe acute pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2008;36:39-43.

- Chen H, Li F, Sun JB, et al. Abdominal compartment syndrome in patients with severe acute pancreatitis in early stage. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:3541-8.

- Weaver JL, Smith JW. Direct peritoneal resuscitation: a review. Int J Surg 2016;33:237-241.

- Smith JW, Ghazi CA, Cain BC, et al. Direct peritoneal resuscitation improves inflammation, liver blood flow, and pulmonary edema in a rat model of acute brain death. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;219:79-87.

- Garrison RN, Conn AA, Harris PD, et al. Direct peritoneal resuscitation as adjunct to conventional resuscitation from hemorrhagic shock: a better outcome. Surgery. 2004;136:900–8.

- Crafts TD, Hunsberger EB, Jensen AR, et al. Direct peritoneal resuscitation improves survival and decreases inflammation after intestinal ischemia and reperfusion injury. JSR. 2015;199:428–434.

- Zakaria ER, Li N, Garrison RN. Mechanisms of direct peritoneal resuscitation–mediated splanchnic hyperperfusion following hemorrhagic shock. Shock. 2007;27:436–442.

- Smith JW, Garrison RN, Matheson PJ, et al. Direct peritoneal resuscitation accelerates primary abdominal wall closure after damage control surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210:658-67.

- Smith JW, Garrison RN, Matheson PJ, et al. Adjunctive treatment of abdominal catastrophes and sepsis with direct peritoneal resuscitation: indications for use in acute care surgery. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;77:393-8.

- Wilson PG, Manji M, Neoptolemos JP. Acute pancreatitis as a model of sepsis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;41:51-63.