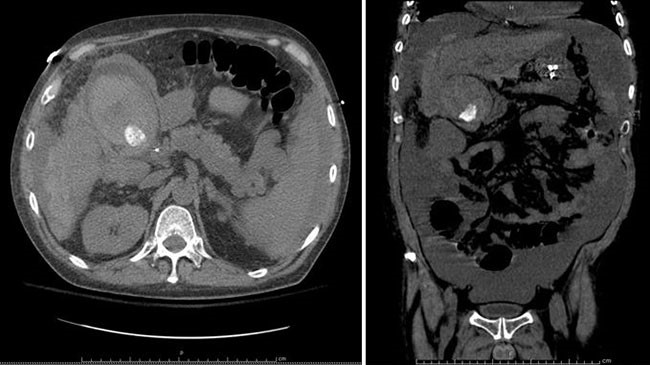

Figure 2. CT abdomen and pelvis with contrast. (A) Axial image demonstrates multiple abscesses (*), free fluid(x), inflammatory changes of the subcutaneous and intra abdominal fat and enlarged pelvic appendix (arrow). (B) Coronal image shows dilated appendix with appendicolith (arrow). Postoperative intramuscular air seen (>).

On hospital day 7, as sepsis resolved, the wounds were clean and exhibited granulation tissue. Washout and wound closure of the medial and lateral leg and partial closure of the lateral thigh was uncomplicated. Likewise, over the following 4 days, the remaining open wounds were sutured closed. No further surgical interventions were performed. On hospital day 28, she was transferred to the rehabilitation floor, then discharged on hospital day 47. The patient's hospital course is summarized in Table 1. An uncomplicated interval appendectomy was performed three months later. Findings at surgery included a long appendix with the midpoint adherent to the retroperitoneum.

| Hospital Day | Procedure | New Findings |

| 1 | Hospital admission MRI of the right thigh Incision and drainage of medial thigh | Multiloculated thigh abscesses, profound muscle and soft tissue inflammatory changes extending to the knee Tissue necrosis, significant fascial inflammation Cultures positive for Escherichia Coli |

| 2 | MRI of right calf Incision and drainage of: right lateral thigh, right lateral leg, medial leg and drainage of medial thigh CT of abdomen/pelvis Interventional Radiology placed 10 French drain for iliopsoas abscess Intubation/ventilation initiated | Inflammation extending to distal leg, fluid in the crural fascia Ruptured appendicitis with intra-abdominal abscess Septic shock |

| 3 | Surgical drainage of iliopsoas abscess with insertion of 3 Penrose drains | |

| 4 | Washout and drainage of thigh and leg incisions | |

| 5 | Weaned off of sedation and pressor support | |

| 7 | Closure of medial and lateral leg incisions | |

| 9 | Closure of lateral thigh incision | |

| 11 | Closure of medial thigh incision with placement of 2 right lower quadrant Penrose drains | |

| 28 | Transfer to rehabilitation floor following wound care | |

| 47 | Discharged with plan for interval appendectomy |

Table 1. Timeline of Hospital Course

Discussion

Ruptured appendicitis with contamination of the ipsilateral lower extremity is recognized in cases of retrocecal appendix, primarily affecting older or immunocompromised patients (Table 2). The retrocecal appendix is in close proximity to the psoas, allowing infection from a ruptured appendix to track along tissue planes following the psoas muscle into the thigh as it inserts on the lesser trochanter of the femur.5 A thigh abscess resulting from rupture of a non-retrocecal appendix positioned in the right pelvis (Figure 2), as in this case, is unreported in the literature.6 Furthermore, ruptured appendiceal abscess tracking along the femoral vessel all the way to the foot is unreported.

| | Age | Abscess Location | Appendix Location | Complications | Treatment* | Survived |

| Edwards 198610 | 76 | Psoas to thigh | Retrocecal | Myositis, necrosis, sepsis | Surgical drainage | No |

| Dheer, 200111 | 57 | Gluteal/abdominal wall to knee | Retrocecal | Myositis, subcutaneous emphysema, necrosis | Surgical drainage and debridement | Not reported |

| El-Masry 200212 | | Psoas to thigh | Retrocecal | | Appendectomy Surgical drainage | Yes |

| Sharma 200513 | 6 | Psoas to thigh | Retrocecal | Myositis, sepsis | Appendectomy Surgical drainage | Yes |

| Ushiyama 200514 | 83 | Psoas to thigh | Retrocecal | Myositis, subcutaneous emphysema | Appendectomy Curettage | Yes |

| Hsieh 20065 | 56 | Psoas to thigh | Retrocecal | Myositis, subcutaneous emphysema | Appendectomy Surgical drainage | Yes |

| Yildiz 200715 | 27 | Inguinal ligament to groin | Retrocecal | Sepsis | Appendectomy Surgical drainage and debridement | Yes |

| Sookraj 200916 | 67 | Psoas to thigh | Retrocecal | Necrosis | Appendectomy Curettage | Yes |

| Lal

201217 | 40 | Gluteal to thigh | Retrocecal | Subcutaneous emphysema | Appendicecotomy

Surgical drainage

Ileotransverse colectomy | Yes |

| English 201218 | 56 | Iliacus to thigh | Retrocecal | Necrosis | Surgical drainage and debridement

Interval appendectomy | Yes |

| Nanavati 201519 | 53 | Gluteal/psoas to thigh | Retrocecal | | Surgical drainage

Ileocolostomy | Yes |

| Naidoo 201620 | 50 | Psoas to knee | Retrocecal | Necrosis, sepsis | Appendectomy

Surgical drainage and debridement | No |

| Van Hulsteijn 20176 | 73 | Iliopsoas to thigh | Retrocecal | Myositis | Surgical drainage Ileoascendostomy | Yes |

| Case Report | 16 | Psoas to foot | Not retrocecal | Myositis, necrosis, sepsis | Surgical drainage and debridement

Interval appendectomy | Yes |

Table 2. Cases of appendicitis resulting in lower extremity abscess

The only predisposing factor in the patient's medical history was dermatomyositis at age 5, treated with steroids and methotrexate. Of the three clinical courses described for JDM (chronic, polycyclic and monocyclic) this patient was categorized as monocyclic due to the successful treatment of JDM with no further recurrences.7 A prospective cohort study found the most common clinical course for JDM is chronic (60%) followed by monocyclic (37%) and least commonly polycyclic (3%).7 She had been in remission and off steroids for seven years. We suspect residual changes in muscle and fascia from the original JDM episode predisposed the patient to infection spread down the soft tissue planes to the foot. Connective tissue fibrosis also may have compromised the normal separation of compartments.8 In this case, MRI evidence of atrophy and fatty deposits may have been obscured by swelling and the fluid signal from edema. While the patient experienced unilateral leg weakness, muscle inflammation, and laboratory values consistent with active myositis, laboratory values did not confirm recurrence of juvenile dermatomyositis.

Conclusions

Although the most common pediatric inflammatory myopathy, JDM still remains rare and clinical implications of remission poorly understood.9 Clinicians must remain cognizant of potential life-threatening complications from JDM even when the disease has been clinically quiescent, and patients are not on steroid therapy.

Lessons Learned

Based on this case experience, we recommend comprehensive imaging to delineate the sites of infection to direct aggressive surgical drainage as necessary to resolve progressive sepsis. Earlier determination of the source of infection, including cultures positive for organisms directing an abdominal or rectal source, allows strategies for drainage to minimize progression.

Authors

Vanessa M Bazan, BS, BBA

University of Kentucky

Lexington, Kentucky

Clare Savage, MD

River City Imaging Associates, San Antonio, Texas

Maria-Gisela Mercado-Deane, MD

River City Imaging Associates, San Antonio, Texas

Joseph B. Zwischenberger, MD, FACS

University of Kentucky

Lexington, Kentucky

Correspondence Author

Vanessa M Bazan

University of Kentucky AB Chandler Hospital

800 Rose Street, MN 265A

Lexington, KY, 40536-0298

Tel: 210-317-5535

Email: vba234@uky.edu

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Huber AM, Giannini EH, Bowyer SL, et al. Protocols for the Initial Treatment of Moderately Severe Juvenile Dermatomyositis: Results of a Children's Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance Consensus Conference. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010;62(2):219-225.

- Martin N, Li CK, Wedderburn LR. Juvenile dermatomyositis: new insights and new treatment strategies. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2012;4(1):41-50.

- Wedderburn LR, Varsani H, Li CK, et al. International consensus on a proposed score system for muscle biopsy evaluation in patients with juvenile dermatomyositis: a tool for potential use in clinical trials. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(7):1192-1201.

- Rider LG, Lachenbruch PA, Monroe JB, et al. Damage extent and predictors in adult and juvenile dermatomyositis and polymyositis as determined with the myositis damage index. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(11):3425-3435.

- Hsieh CH, Wang YC, Yang HR, et al. Extensive retroperitoneal and right thigh abscess in a patient with ruptured retrocecal appendicitis: an extremely fulminant form of a common disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(3):496-499.

- van Hulsteijn LT, Mieog JS, Zwartbol MH, et al. Appendicitis presenting as cellulitis of the right leg. J Emerg Med. 2017;52(1):e1-e3.

- Stringer E, Singh-Grewal D, Feldman BM. Predicting the course of juvenile dermatomyositis: significance of early clinical and laboratory features. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(11):3585-3592.

- Corr DT, Gallant-Behm CL, Shrive NG, et al. Biomechanical behavior of scar tissue and uninjured skin in a procine model. Wound Repair Regen. 2009;17(2):250-259.

- Feldman BM, Rider LG, Reed AM, et al. Juvenile dermatomyositis and other idiopathic inflammatory myopathies of childhood. Lancet. 2008;371(9631):2201-2212.

- Edwards JD, Eckhauser FE. Retroperitoneal perforation of the appendix presenting as subcutaneous emphysema of the thigh. Dis Colon Rectum. 1986;29(7):456-458.

- Dheer AK, Carr B, Morrison P, et al. Appendicular abscess and a swollen knee. Lancet. 2001;358(9290):1366.

- El-Masry NS, Theodorou NA. Retroperitoneal perforation of the appendix presenting as right thigh abscess. Int Surg. 2002;87(2):61-64.

- Sharma SB, Gupta V, Sharma SC. Acute appendicitis presenting as thigh abscess in a child: a case report. Pediatr Surg Int. 2005;21(4):298-300.

- Ushiyama T, Nakajima R, Maeda T, et al. Perforated appendicitis causing thigh emphysema: a case report. J Orthop Surg. 2005;13(1):93-95.

- Yildiz M, Karakayali AS, Ozer S, et al. Acute appendicitis presenting with abdominal wall and right groin abscess: a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13(26):3631-3633.

- Sookraj KA, Bowne WB, Ghosh BC. Perforated appendicitis presenting as a thigh abscess. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208(6):1142.

- Lal S, Gupta R, Gaharwar APS, et al. Thigh Abscess is an Unusual Presentation of the Perforation of Retroperitoneal Appendicitis. J Clin Diagn Res. 2012;6(3):457-459.

- English J, Theis JC. Thigh pain--an unusual presentation of ruptured appendicitis. N Z Med J. 2012;125(1364):102-106.

- Nanavati AJ, Nagral S, Borle N. Retroperitoneal perforation of the appendix presenting as a right thigh abscess. Case Rep Surg. 2015;2015:707191.

- Naidoo S, Du Toit R, Bhyat A. Perforated appendicitis presenting as a thigh abscess: a lethal combination. S Afr J Surg. 2016;54(3):43.