Editor’s note: The following is an edited version of the Olga M. Jonasson, MD, Lecture that Dr. Anderson delivered at Clinical Congress 2017 in San Diego, CA. The presentation has been modified to conform with Bulletin style.

I am most grateful to the American College of Surgeons (ACS) Women in Surgery Committee for asking me to give this lecture. I am glad to have the chance to honor the surgeon who was a heroine to so many medical students, residents, and surgeons of both genders, Olga M. Jonasson, MD, FACS.

Dr. Jonasson’s impact

Olga had a unique character. She was a great technical surgeon whose many sayings in the operating room in her unexpectedly high voice were remembered and repeated by her former residents, all of whom held her in the highest esteem. She was the first woman in the U.S. to head a major department of surgery, going from chief of surgery at Cook County Hospital, Chicago, IL, to chair of the department at Ohio State University, Columbus. She left that post to become Medical Director of the ACS Education and Surgical Services Department, as it was then called, a post she held for the rest of her career. She ought to have been the first woman President of the College, but staff members were excluded from consideration for that position.

It was during her tenure at the ACS that I met Olga, when she tasked a number of us to search out women who should be but were not in leadership positions in American surgery. This came about when one of the members of the membership committee of the American Surgical Association (Jonathan L. Meakins, MD, FACS) became ashamed of the dearth of women in that organization (there were only three of us at that time) and came to Olga for a solution. This was a productive exercise for us and led to many more women being elected to prestigious societies and to reaching leadership positions in the College. I was so proud to call her my friend.

A tomboy in Victorian England

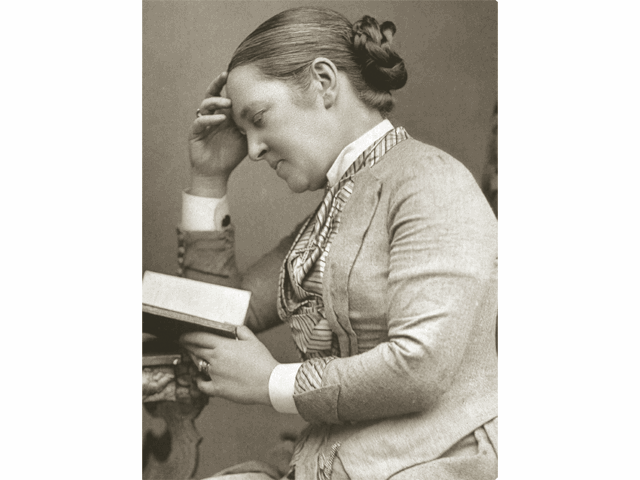

I am going to speak today of an earlier pioneer for women in surgery, one with whom I feel a great affinity, although she was born more than a century before me but whose career had some similarities to my own. I have chosen the first woman surgeon in England, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, who piqued my interest several years ago because of our common last name and common heritage.* Perhaps it is arrogant to compare myself with a woman who certainly overcame many more obstacles than were placed before me and who pioneered the way for generations of women who were determined not to allow the shibboleths of their day to deter them from their desire to be surgeons. If so, I hope that this audience will forgive me.

Elizabeth Garrett was born in June 1836, the year before Victoria became queen of the British Empire. She was born in London’s East End, the second child of a pawnbroker who bought and sold goods in this poor section of London. It was undoubtedly expected that a boy would be born, since the Garretts’ first child was a girl. But Elizabeth never fit the mold of a proper English girl in the Victorian era. She was a tomboy.

Expected paths in the 1800s

| Boy | Girl |

| School education | Learn sewing and music at home |

| University education | Hah! |

| Choose a profession | Learn perfect manners |

| Get married, have children but never do housework or child care | Get married and have children |

| Spend each day at work | Spend each day sitting in the drawing room, or looking after children and home |

| Share his opinions with others | Keep her opinions to herself, unless talking about children or home |

I was also the second child and second girl, and I know for sure that my father had wished for a boy. My biological mother died in childbirth when I was 16 months old and my father lost, besides his wife and our mother, her twin babies who were boys. I have wondered but never asked my father if he would have encouraged my career in medicine and surgery had the twins lived. I believe that he would, as he was in many ways, like Mr. Garrett, a man before his time. Elizabeth’s father believed wholeheartedly in educating all his children to the same extent and Elizabeth was sent to a private girls’ school, an unusual event for girls of that time. Boys went to public school (in England, these were inexplicably the private schools), whereas girls were educated at home by a series of governesses. There was a huge difference between boys’ and girls’ expectations, education, and life experiences in that era (see sidebar above).

Mr. Garrett did well in business and moved to a large country home in Aldeburgh, Sussex, as his business expanded. He made a fortune, so Elizabeth had the advantage that she never had to scrape and save for her medical education. I, on the other hand, had to win scholarships to go to medical school. However, Elizabeth’s father did not believe that women should be educated after high school or have a career and at first did not take kindly to her wish to be a physician. Her mother never was reconciled to her daughter having a career, particularly in surgery, and there my experience was similar. For some reason that I never learned, my stepmother was very much opposed to my going to a university in the first place, never mind medical school.

Introduction to surgery

But I am getting ahead of myself. After Elizabeth left her private school for girls (there were no co-ed schools then) at the age of 15, she stayed in the family home for nine years, helping to raise her younger siblings and developing a deep and lasting friendship with her older sister that is reminiscent of the relationship I have with my older sister. But Elizabeth was bored, and her intellect was unused. When she was 22, a group of women published a magazine for women, English Woman’s Journal. Among these women was one Emily Davies, who became a dear friend. She invited Elizabeth to hear a lecture given by Elizabeth Blackwell, MD, whom some in the audience will recognize as the first woman physician in the U.S. Dr. Blackwell emigrated to the U.S. from England with her family and pursued a medical career, culminating in a medical degree from Geneva Medical College (now Hobart and William Smith Colleges) in upstate New York, which was practically impossible in England or the U.S. She wanted to be a surgeon but lost an eye to infection and had to “settle” for a career in medicine. She expected that the women in her audience all wanted to be physicians, and she encouraged Elizabeth Garrett to pursue her dream. From then on, Elizabeth was determined to get a medical degree and practice medicine and become a surgeon.

My own introduction to surgery was not at all traumatic. In my family, there was no revulsion about women being surgeons as there was in Victorian families. I was inspired by a visit to the newly reopened Manchester Art Gallery after World War II; my sister and I were taken there by a beloved aunt, a very cultured woman whose own career as a teacher was handicapped by the restrictions on women in the era of George V.

At the art gallery, I saw a picture simply labeled “Theatre” in pencil with a wash of green, by Barbara Hepworth, better known in England as a sculptress. I apparently stood in awe before this drawing for a long time. Whether this sealed my career choice, I don’t know, but I have loved that picture for a very long time. My fantasy life as a young girl always involved playacting being a surgeon.

Medical education and training

Miss Garrett’s first venture into medicine was to enter the Middlesex Hospital in London as a nurse. She could not get into an English medical school, so she chose to enter a medical education through the back door, as a nursing student. I, too, had a delay in entering medical school, which in Europe, then and now, was directly after high school, though this was not for the same reason as Elizabeth’s difficulty. I was due to take entrance exams (these were advanced, or A-level, exams, required for any university entrance) and hopefully do well enough to win a state scholarship to enable me to pay medical school fees. The day before the exams were due to start I developed epigastric pain, which migrated to my right lower quadrant. After considerable delay of the whole summer, due to our general practitioner’s lack of diagnostic ability, my retro-caecal appendix was removed. I missed the exams, of course, and had to spend an extra year in high school before they were available again. This was one of my best years, as I spent the time relearning Latin and advanced mathematics, chemistry, physics, and biology, as well as taking other fun classes. During that year, my headmistress encouraged me to apply for and take the separate entrance exams for Oxford and Cambridge. This is where the requirement for Latin came in—I doubt it is required any longer. I was successful at Cambridge and entered Girton College at that university.

What does that have to do with Elizabeth’s career? As it turns out, a lot. Girton College was founded by Emily Davies, Elizabeth’s lifelong friend and mentor. Elizabeth stayed involved with this progressive women’s college, the first resident college for women. Like all the Cambridge colleges, it was initially only for girls or only for boys, although most now are co-ed. In fact, my first room was in the Emily Davies Court. An anecdote that has little to do with Elizabeth: My rooms in my first and second years were on the ground floor, a convenient entrance to girls who stayed out after curfew and who would be fined if they came through the front door, which was guarded by a diligent ex-policeman with a very good memory. A knock on the window was frequent; the culprit climbed in, said goodnight, and went to her own room. It was rather disturbing for one’s sleep, so I was glad to be on the first (American second) floor my third year.

Back to Elizabeth. At the Middlesex Hospital, she joined the medical students on their rounds, and after a while all pretense of being a nursing student was dropped. During this time, she met a physician named John Ford Anderson who was impressed by the young woman’s depth of knowledge, and they formed a friendship that was to influence her life in the future in a very special way (I will come back to that in a little while).

For Elizabeth, her troubles began when it was obvious that she had aspirations to be a physician. The all-male student body rebelled at having a woman rounding with them and threatened to leave. The teachers were entirely dependent on the students’ fees, and so they felt they had to dismiss her. Multiple applications to medical schools were made without success, and so she took an alternate path and applied for permission to audit lectures and take the exam for the license of the Society of Apothecaries, a substitute for the medical degree she craved. She attended lectures given by a member of a very famous family, the Huxleys. T. H. Huxley, the progenitor of this large and brilliant family, renowned for their research in physiology and writing to this day, said: “Let us have sweet girl graduates by all means. They will be none the less sweet for a little wisdom; and the golden hair will not curl less gracefully outside the head by reason of there being brains within.”† One of Huxley’s descendants taught me physiology at Cambridge.

I, on the other hand, never was subjected to prejudice from my fellow medical students, and it was a rare fellow surgical resident who resented my presence. My medical school class in Cambridge had only eight women, but no distinction was made between the men and the women, other than the women did not have to bare their chests in the surface anatomy class. A few students put out the rumor that the men were doing our dissection for us (as, of course, it was perfect), but that falsehood died a natural death when we were observed.

In 1863, Elizabeth was 27 years old, and she again enrolled as a nurse, this time at the London Hospital. She was taken under the tutorship of an orthopaedic surgeon and learned to dissect the human body. Her piecemeal education enabled her to become licensed as an apothecary.

My own medical education was also divided. I met my American husband in the dissection room at Cambridge and transferred to Harvard University School of Medicine, Boston, MA, after three years, starting with the second year there and earning my medical degree in 1964—a total of six years of medical school. I never took the English final exams.

Elizabeth still had ambitions of becoming a surgeon, but in the meantime, she opened a dispensary for the poor in East London, close to the house where she was born. England began to take notice of this determined woman, but many of the comments about her by the British Medical Association (BMA) and The Lancet were scathing and cruel. But Punch, that unusual and often avant-garde magazine, published cartoons of her that were favorable. Her only patients at first were women and children, but later she had a wide patient base, including many men.

Still not satisfied, she continued to apply to medical schools, all of which rejected her. It came to Queen Victoria’s ears that this intrepid woman was trying to get a medical degree. The Queen, herself a pioneer, having been the first in England to have a child under chloroform anesthesia, became angry after she learned of a supposedly secret visit to Elizabeth by her eldest and more modern daughter. Victoria was very unsupportive of women for her entire life. There is a syndrome of minorities, rare but still existing, of what I call the “teacher’s pet syndrome”—someone who believes that as a minority, he or she has no obligation to foster others belonging to the same minority and often actively opposes them. I guess they enjoy being the minority in a field dominated by white males.

So, after multiple rejections by the English and Scottish medical schools, Elizabeth had to go to the University of Paris, France, for her degree. That institution did not want to admit her, but she drew the attention of the Empress Eugenie of France, who insisted. In fact, at that time, the Empress was presiding over the French Council of Ministers, the deciding body, during the illness of her husband, Napoleon III, and she mandated the entrance of women to medical training at the University of Paris. Elizabeth came first in the final exams out of a class of eight with a pass rate of three. So, finally, she became a bona fide physician.

A controversial figure

There were no formal residencies in surgery in the 19th century, and that was perhaps just as well for the time, as Elizabeth was then on her own to do as she liked. One of her former tutors at the London Hospital decided to open a children’s hospital in London’s East End. One of the board members initially was opposed to her becoming a staff member of this hospital, but Elizabeth was invited to give a presentation to the board. The board member was impressed with her presentation and withdrew his opposition. His name was James Skelton Anderson, the brother of John Ford Anderson whom I mentioned earlier. Undoubtedly, Skelton Anderson was influenced by his brother’s opinion of Elizabeth. The subsequent friendship with Skelton led to their marriage in 1871. During her time at the children’s hospital, the now Mrs. Anderson performed surgery in addition to running medical clinics and a dispensary that she named after Saint Mary. She often wrote about her nervousness before a major operation, a feeling I shared with her for my entire practice. As education became more formalized in England, she served on the London School Board and was a lively though often controversial member.

When she and Skelton Anderson made it known that they would marry, Elizabeth again experienced prejudice. It was widely believed at that time that women who married should stay home and become full-time mothers. So, it was expected that she would withdraw from practice and that would be a “waste of her education” and the waste of a place that should have been occupied by a man. I was also questioned closely in interviews on a number of occasions with queries such as: “You are getting married (or you are married), and you’ll quit if you have children. Are you planning to have children?” I always thought this was impertinent and usually replied, sometimes rudely, that it was none of the enquirer’s business.

It is not known how Elizabeth responded to such questions, but she was known to have a sharp tongue and was not afraid to put people in their place, sometimes to her own disadvantage—just like myself. Unlike me, she did go on to have three children: Louisa, her first-born at the age of 37, another girl, who died of meningitis, and Colin, her only boy. Her husband was always supportive, and the marriage lasted until his death from a stroke in 1907. They were two independent people who pursued their own separate interests but were bound together by love and affection.

In 1872, St. Mary’s Dispensary became The New Hospital for Women, largely due to Elizabeth’s efforts. At first, there was reluctance to allow her to perform surgery at the hospital. Indeed, she had the opportunity to perform the first oophorectomy done by a woman, but the board would not permit her to do this onsite. Perhaps they were afraid that they would be blamed if anything went wrong. Undaunted, Elizabeth set up a private house with an operating room, and the operation was successful. There was no opposition thereafter, and she performed many operations during the rest of her career at the hospital. Surgery in private houses was not unknown, even in the 20th century, though it involved major operations less and less. In fact, George VI had his pneumonectomy for carcinoma of the lung in Buckingham Palace. I remember my sister having dental work done under anesthesia, given by our general practitioner, which was performed on our kitchen table. I was excluded from observing this procedure, though I remember that I sneaked in.

By the 1870s, the principles and practice of antisepsis, promulgated by Lord Joseph Lister, were widely used and automatic infection of open wounds diminished substantially. Elizabeth stayed at The New Hospital for Women until she retired. After her death, the hospital was renamed the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Hospital for Women, and in 1948 it was merged into The Royal Free Hospital for Women when the National Health Service was formed.

Acceptance

The final bastion of male supremacy, the BMA, finally recognized that it was behind the times, and in 1873 admitted Elizabeth Garrett Anderson as its first and, for 19 years, only female member. A number of papers she wrote were published in the British Medical Journal, though her numerous lectures on diverse subjects were never memorialized. She became in succession the president of the New Hospital for Women and the Medical School, and Mayor of Aldeburgh. She also became president of the East Anglia branch of the BMA. I have shared with Elizabeth the privilege of being the first woman to be given several honors, my own within the pediatric surgical community and in this College, my medical home.

Elizabeth was instrumental in gaining the admission of women to the Royal College of Physicians, which reminds me of the efforts of my colleagues (all MD, FACS) ACS Past-President Patricia J. Numann (who at Clinical Congress 2017 was presented as an Icon in Surgery); Patricia K. Donahoe; and ACS Foundation Chair Mary H. McGrath, among many others over the years, after we were formed into a group by Dr. Jonasson with the objective of identifying “worthy women.” But Elizabeth, like me, was strenuously opposed to quotas. I have always felt that if I was refused to attain a position I was qualified for, it demeaned the position, but if I was appointed only because I was a woman, it demeaned me. I never enjoyed being the token woman any more than Elizabeth did.

Mrs. Anderson, as she would have been known in England, a title without the appellation “doctor” that to English surgeons is an honor (stemming from the time of the barber-surgeons), lived for 16 years after her retirement at the age of 65 in 1901. She spent the rest of her life surrounded by family and beloved of her colleagues, her mentees, and her community. She never attained any national honors, though she clearly deserved them, because Queen Victoria never forgave her for stepping out of the mold of the Victorian lady and, horrors, getting a medical degree from France. Her son, Edward VII, did not rectify his mother’s omission. Ultimately, Elizabeth became forgetful and developed progressive dementia, a fate I hope to avoid. She died in 1917, at the age of 81.

Clearing the path for other women

I have stressed the early struggles of this great pioneer of women. Once she had obtained medical training, her social position and her wealth allowed her to do many things that a poor woman could not accomplish. For all her life, she helped those women coming after her and, along with her friendship with Emily Pankhurst, the famous suffragette, helped to obtain the vote for women and better their position in society, regardless of whether they were physicians. She certainly paved the way for us all, always striving to reach equality but not receive special privileges.

I will close with Elizabeth’s words: “I ask you to turn your thoughts to the future and to consider where further progress is most wanted.”† We must guarantee that future patients will receive not only the latest in technological advances but the best in humanitarian care that transcends gender, ethnicity, religion, and specialty.

*Thomas I. The World’s First Women Doctors: Elizabeth Blackwell and Elizabeth Garrett Anderson. London, England: Collins Publishers; 2015.

†Manton J. Elizabeth Garrett Anderson. New York, NY: E.P. Dutton and Co. Publishers; 1965.