Change is inevitable, and medicine and surgery are lagging behind other sectors of society. This article delves into the parallels between ongoing public battles for equity and inclusion to struggles facing various professionals with lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and other sexual identities (LGBTQ+); minorities; and women.3

#BornThisWay

In 2011, Lady Gaga, a pop music artist, released the song “Born This Way.” The lyrics evoke feelings of freedom, empowerment, and love of oneself. The song quickly became the latest anthem for the LGBTQ+ community.4 #BornThisWay continues to represent individuals who are trying to break free of the stereotypes and stigma of their sexual and gender identities.

The implications of bias and gender-based harassment cannot be overstated. For example, overt discrimination as well as microaggressions against LGBTQ+ individuals in the sports world are associated with significant influences on athletes’ educational and athletic outcomes, depressive symptoms, substance use and abuse, and suicidal ideation.5 In the same light, negative experiences in the workplace and in health care are associated with lower self-esteem, increased stress and anxiety, feelings of isolation, headaches, poor appetite, and eating disorders.6,7 Residents who experience discrimination reported higher rates of burnout (51.6 versus 40 percent, p <0.001), thoughts of attrition (16.2 versus 10.1 percent, p <0.001), and suicidal thoughts (6.5 versus 3.8 percent, p <0.001).1

An evaluation of the factors abetting discrimination reveals ignorance as the most basic cause. Lack of knowledge of the various gender and sexual identities, and the implications of bias against them, forms the basis of harassment and microaggression. In the setting of a surgical training program, the source of discrimination is not just fellow health care workers, but patients and their families as well.1 Part of the problem lies in how the health care environment is portrayed to the public; until recently, the public misrepresentation of the medical workforce has been cisgender (gender identity aligns with sex assigned at birth), white, and male. This image directly correlates with the negativity that minority health care professionals often experience.8 Thankfully, change is afoot.

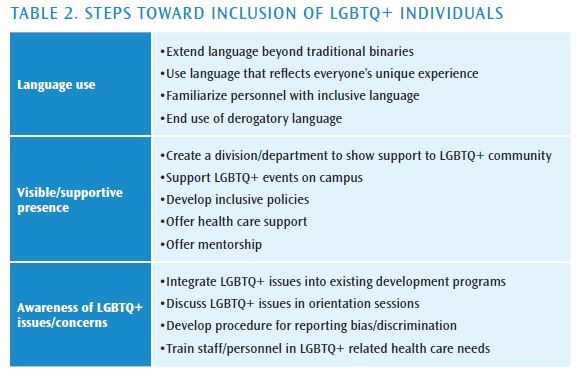

The past two decades have seen several prominent personalities come out openly about their gender and sexuality and begin to advocate for LGBTQ+ rights. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the athletic arena. This includes the work done by soccer World Cup winner Megan Rapinoe, major league baseball player Billy Bean, and the first openly transgender triathlete Chris Mosier.9 Led by these vocal role models, the sporting industry has been at the forefront of societal changes—inclusion and empowerment, acceptance, and compassion. Table 2 highlights several of the practices that the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) has adopted to promote a positive campus climate for LGBTQ+ athletes.10

One crucial NCAA practice involves creating a visible and supportive presence for the LGBTQ+ community. Acceptance of LGBTQ+ individuals by both their families and their teams leads to greater self-esteem, improved health, and prevention of depression, suicide, and other self-harming behaviors.11 Another important step is enhancing the cultural awareness of educators, making an effort to extend language beyond traditional binaries, and integrating LGBTQ+ issues into existing educational programs.12 Guidance and mentorship are key to surviving in an environment of bias and microaggression. The medical and surgical communities could learn a lot from this approach, by incorporating gender sensitivity training, by providing visible support and mentorship to LGBTQ+ members, and taking steps to eradicate discrimination based on gender identity.

#OscarsSoWhite

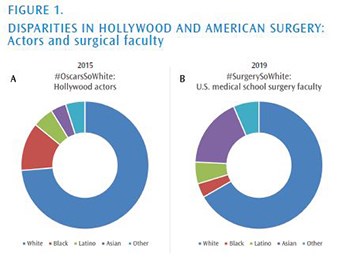

#OscarsSoWhite is a social justice campaign that was started in January 2015 in response to the fact that all 20 acting nominations of the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences were awarded to white actors. The movement gained even more momentum when, a year later in 2016, all 20 acting nominees again were white actors.13 The movement eventually expanded to call out the underrepresentation in the motion picture industry, both on and off screen, of multiple marginalized groups. A large part of the problem was that, as of 2012, of almost 6,000 voting members of the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences, only 6 percent were people of color and 23 percent were women.14 In 2019, these numbers improved; today, the academy has almost 8,000 voting members, 16 percent of which are people of color, and 31 percent are women.

Furthermore, despite the fact that in 2019, when four of the acting nominations and three of the eventual winners were people of color, 2020 again was notable for its lack of diversity. The question then becomes, how do we not only promote change, but also sustain it?

The issue of diversity extends beyond who is celebrated in the movie business to who is portrayed in the movies. According to a 2016 report released by the Annenberg Foundation and the University of Southern California (USC) Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, in the top 100 top-grossing films of 2015, 73.7 percent of the characters were Caucasian, 12.2 percent African American, 5.3 percent Latino, and 3.9 percent Asian. These percentages had remained unchanged since at least 2007. The issue also encompasses who holds one of the most coveted positions on the movie set; in 2015, only four of the 107 directors were of African descent (3.7 percent), and six were of Asian descent (5.6 percent). Across 886 directors from 2007 to 2015 (excluding 2011), only 5.5 percent were black and 2.8 percent were Asian.15

Many of these same disparities are mirrored in American surgery (see Figures 1 and 2). Based on 2019 U.S. census data, 13.4 percent of the population is black, 18.3 percent is Hispanic or Latino, and 5.9 percent is Asian.16 However, only 3.6 percent of the U.S. medical school faculty members are black and 5.5 percent are Latino.2