Gastrostomy tube (G-tube) placement is often a crucial component in a medically complex child’s care and one of the more common procedures performed at children’s hospitals; however, approaches to patient counseling and postoperative management for this procedure varies. Families often agonize over the decision and worry about their ability to care for their child after the tube is placed. Complications, such as early dislodgement, result in emergency department (ED) visits and potential readmissions, and lengths of stay (LOS) and feeding advancements vary between different centers and different providers.*

All these factors affect quality of care, patient and caregiver satisfaction, and health care costs. It has been shown that a standardized pathway for feeding tube placement can result in significant reduction in postoperative LOS and fewer ED visits.† Appropriate preoperative family education is necessary to understand the procedure, but perhaps more importantly, to prepare them for what to expect once their child has a G-tube. Skills videos, including the American College of Surgeons’ (ACS) Feeding Tube Home Skills Program for caregiver education can be an easily accessed and is an efficient tool to help improve confidence levels, particularly for families with low literacy levels.‡

G-tube referrals at Mary Bridge Children’s Hospital, MultiCare Health Systems, Tacoma, WA, before the intervention described in this article were a point of frustration for caregivers, providers, and the nursing staff. We experienced confusion on the part of caregivers, missing or incomplete preoperative work-up or education, delays in scheduling, conflicting instructions on postoperative feeding plans, and frequent ED visits resulting from dislodgement, feeding intolerance, and conflicting patient education.

There was wide variation among surgeons on postoperative feeding advancements and LOS, particularly on the weekends because of lack of coordination with home health services. The cost of in-person teaching by our pediatric gastroenterology (GI) clinic nursing team was becoming unmanageable and created an additional office visit and cost for families and caregivers. Early in our participation in ACS National Surgical Quality Improvement Program-Pediatric (ACS NSQIP®-P), we learned through discussion with other centers that our LOS was longer than at other comparable hospitals.

Initiating the QI activity

Mary Bridge Children’s Hospital is a community-based, 82-bed, Level II trauma center pediatric hospital that is part of a larger, 1,802-bed, integrated health system located in the Pacific Northwest. With more than 30 pediatric specialties, our hospital and its network of primary care, specialty care, therapy, and urgent care visits serve more than 330,000 children each year. The Leapfrog Group named Mary Bridge Children’s Hospital one of the “Top Children’s Hospitals” in 2018 and 2019.

Patients requiring outpatient G-tube placements were noted to have wide variations in pre-consultation education, family preparedness, and completion of necessary diagnostic procedures, which resulted in longer clinic visits and delays in surgical scheduling. This situation led to family and provider dissatisfaction. In addition, variation was noted among the pediatric surgeons regarding postoperative education, feeding plans, and LOS. Having previously completed a successful quality improvement (QI) effort to standardize appendectomy care with improved patient satisfaction and LOS, the pediatric surgeons turned their attention to outpatient G-tube placements as their next area of focus.

Pediatric surgery teamed with another key stakeholder, pediatric GI, to decrease costs within the clinic, the number of unnecessary patient visits, and returns to the ED. The pediatric surgeons and pediatric gastroenterologists formed a task force to analyze the state of outpatient G-tube placements. Multidisciplinary teams of physicians, advanced practice providers (APPs), nursing staff, clinic medical assistants, and registered dietitians were developed to review steps in the process and to identify potential areas of improvement. The NSQIP-P Surgical Champion served as project manager, leading the task force.

The task force determined that QI opportunities spanned the entire process—from the initial pediatric GI consultation visit generating the referral to pediatric surgery through the postoperative pediatric surgery clinic visits. The multidisciplinary teams began working the improvements into their respective process pieces.

Implementing the QI activity

Several process pieces were identified as primary areas of focus: preoperative referrals and scheduling, patient education, and postoperative management.

Two areas of focus with regard to preoperative referrals and scheduling included the GI clinic referral process and clinic scheduling and the preoperative visit. The GI clinic referral process consisted of a pediatric gastroenterologist, pediatric surgeon, surgery clinic registered nurse, and GI clinic registered nurse. This team developed best practices for referrals and coordination between clinics, including the completion of a fluoroscopic upper GI series before being seen in the surgery clinic.

The surgery clinic scheduling and preoperative visit team was composed of a pediatric surgeon, surgery clinic registered nurse, and surgery clinic medical assistant. This team developed a standardized case request for surgery scheduling and a process for operations to be scheduled before clinic discharge, including postoperative two- and six-week follow-up visits.

Patient education centered on development of a standardized G-tube education video. The task force created a patient education video for caregivers to view at home preoperatively. The video was developed by Mary Bridge Community Services, a pediatric gastroenterology provider, a pediatric surgeon and APP, and nursing staff from both the GI and surgery clinics. A pediatric surgeon and the nursing staff from both clinics provided the on-camera education. Several families also shared their stories. The video was made available online or as a disc checked out from the clinic. The video is now available in English and Spanish.

In addition to the video, caregiver education handouts and a post-test were created to ensure comprehension of the materials. The posttest is used to identify families that need additional education, which the GI clinic nursing team provides either by phone or in the clinic.

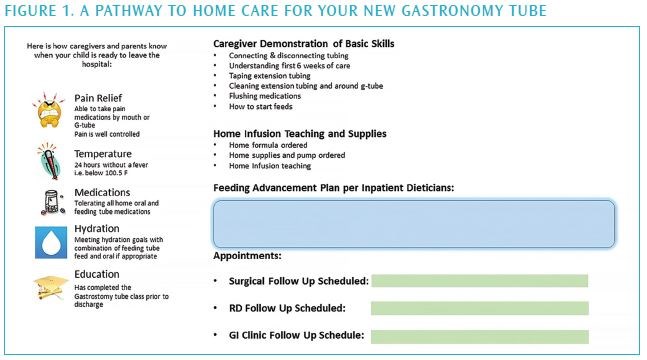

We also provided bedside nursing education. A G-tube “Pathway to Home” flyer was created to educate inpatient nursing staff on postoperative and discharge teaching for caregivers (see Figure 1). Surgery clinic APPs conduct classes during the annual surgery super user pediatric surgical skills nursing program and in the registered nurse residency program.