New visit billing has been greatly facilitated by the January 2021 E/M billing changes. Reimbursement is now based on time and complexity alone, and the cumbersome review of systems and specific examination requirements have been removed; both of these changes are particularly impactful in telemedicine billing. The COVID-19 pandemic experience confirmed that remote encounters facilitated via audiovisual technology can count toward the postoperative visit. These visits fall under the global period and, therefore, are not billable events. This situation always has and will continue to represent a real opportunity for telemedicine growth after surgical care. The PHE telephone waiver is in place so that audio-only visits are possible, but many expect the telephone-only provision to be discontinued when the PHE expires.

Remote patient monitoring billing is more complex because many codes (such as chronic care management codes) require a monthly copayment. Furthermore, specific time documentation must be included to bill for asynchronous monitoring data. At present, interpretation of real-time data by a call center (to ensure safety) is a considerable challenge to generating meaningful revenue. Emerging codes and opportunities for billing of remotely transmitted data and self-entered data exist, but at this point, the time and workflow make this approach less optimal to creating a real revenue stream. It is expected that this area will continue to evolve and become a more significant revenue opportunity.

Peer-to-peer evaluations were billable before the pandemic and continue to be so under the Interprofessional Consult Codes. Surgeons can convey a second opinion to a local physician and couple it with peer-to-peer medical licensing. Most states offer this type of cross-state, instance-based licensing opportunity.

Third-party payor reimbursement for telemedicine remains an active issue and more than 40 states have laws in place that govern private payor telemedicine reimbursement. Payment parity remains a challenging topic as payors view telemedicine as a service with less overhead and hence hold the view that it should not be paid on par with in-person encounters. Physicians, on the other hand, believe that their sunk costs and overhead are not variable. (Sunk costs is a business term that refers to money already spent and that cannot be recovered.) In the end, payment parity is critical for adoption and utilization.

Regulatory environment, interstate issues

Physicians must be licensed to practice in every state in which they practice, including delivery of telehealth services across state lines. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the regulations prohibiting practice across state lines were relaxed, which facilitated the development of surgical virtual clinics. The practice restrictions across state lines are governed by the states, and this situation is unlikely to change permanently any time soon. The Federation of State Medical Boards has a compact in place to facilitate multi-state licensing, which is expanding, but still requires work to obtain. State and federal legislators are facing a growing demand to reexamine limitations on cross-state licensing.6 Although the urge to expand access for patients and providers is obvious, a national license would present potential risks, such as a bullish telemedicine company or delivery system with nationally licensed physicians having wide-open access to regional provider referral networks and patients.

Another key regulated area is the “originating site” for telemedicine, which is defined on the basis of where the patient is located at the time of the telemedicine encounter. For example, in a video visit conducted with patients in their own homes, the patient’s home is the originating site. The originating site historically was limited by both rurality and specific locations, such as the hospital and physician office. There are a few minor exemptions, such as telestroke carts, end-stage renal disease, or substance abuse care, but, by and large, the PHE has enabled physicians to deliver significant amounts of care at home. Legislation is in progress to cement the originating site waiver under the PHE, which is a key area for the ACS to support. The site waiver will be a major determinant of expanded access to surgical telemedicine.

Innovations

Telemedicine is not a replacement for, but rather an enhancement to, in-person care. The next section reviews opportunities for innovations in patient care, interdisciplinary communication, and education.

Promote patient self-care management and monitoring

Existing technology allows for remote patient care via real-time (synchronous) encounters like video visits or telephone calls, or asynchronous encounters such as patient portal messaging, secure texting, or e-mail, where information is exchanged when convenient for both parties. Preoperative preparation may include engaging with patients on weight loss and smoking cessation through goal setting and electronic reminders.

Smartphone or web-based apps can provide a secure real-time forum for physician-patient communication centered on patient-generated health data.7 Bluetooth-enabled devices, such as body composition scales, fitness trackers, and blood pressure, pulse, and glucose monitors can link to the patient’s smartphone for data transmission or communicate directly with the EHR. Alternatively, screenshots of the measurements can be obtained and transmitted to the physician via secure messaging or EHR patient portals. Postoperatively, patients can record vital signs, share wound photographs, and report drain output quality and quantity, facilitating better-quality data for postoperative triage and more personalized follow-up care. For patients who travel longer distances to seek care, these elements may improve local care coordination, assist in earlier identification of surgical complications, and even avoid unnecessary in-person travel for wound evaluation.

Adoption of telehealth can be particularly useful for surgical specialties that manage chronic diseases, such as obesity, in which a physical exam is not always necessary. In the context of bariatric surgery practice, engaging patients via remote monitoring has been shown to increase and accelerate preoperative weight loss, decrease program drop-out rates, and decrease time spent in preoperative clinic visits. Although the effect of telemedicine on surgical outcomes has not been widely investigated, early evidence suggests a potential benefit to some surgical specialties.8-10

Improving quality of care

As newly trained surgeons begin independent practice, they sometimes face unexpected challenges in the operating room and uncommon situations/diseases in the clinic. Senior partners or disease-specific experts might not always be available for consultation or just-in-time mentoring, especially in the nonacademic setting. In some rural areas, the nearest surgeon colleague may be 100 or more miles away.

Some surgeons use the ACS Communities to review decision-making on complex cases. Telemedicine provides the opportunity for real-time, peer-to-peer consultation. With the increasing availability of more sophisticated equipment and telecommunication platforms, remote one-on-one intraoperative telementoring also is feasible. Future ACS-based programs could include real-time support from a panel of surgical experts or even formal evaluation of skills as surgeons look to document their expertise and expand their certification.

Care coordination is central to managing patients with complex diseases, such as cancer, or patients facing a long recovery after an unexpected emergency operation. Video-based intra-facility tumor board meetings with secure sharing of patient imaging and pathology allow for improved care coordination and multidisciplinary collaboration. Dependency on long-term nutritional support, complex wound or ostomy care, and physical rehabilitation increases the need for multidisciplinary communication across both space and time. Surgeons often are responsible for connecting multiple post-discharge support services; video conferencing multiple providers both pre- and post-discharge with social worker and nursing support now is feasible and can provide much-needed patient-centered care planning and follow-up. Even emergency consultations can be improved by incorporating telehealth technology. Particularly in this time of resource constraint, it is especially valuable to evaluate imaging and other patient data with a direct video connection to referring physicians to triage the most appropriate emergency transfers.

Surgical telemedicine advocacy

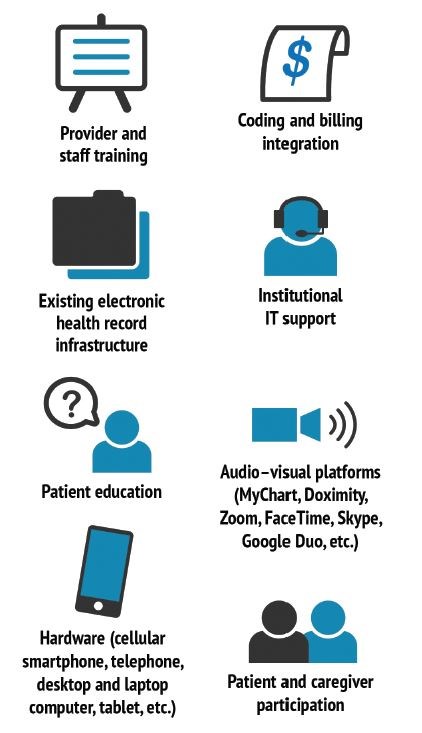

As the use of telemedicine grows in surgical practices, the College has a critical role to play in promoting thoughtful, feasible workflow integration. As we have learned from challenges encountered in adoption of EHR integration, novel means of engaging in and documenting patient care can create an undue burden on physicians and health systems. The very features that make expanding existing care services with telemedicine so attractive—ease of use, increased direct patient access to providers, portability—threaten to overwhelm providers if the integration into existing clinical workflow is mismanaged.

We must establish standards for remote care monitoring so as to set reasonable expectations for response time, as well as what can and cannot be provided virtually. As in any other form of patient care, surgeons require infrastructure and administrative support to use telemedicine efficiently. Providers require support staff, time and coverage systems, and reimbursement mechanisms to integrate telemedicine into their practice. Likewise, telemedicine patients (like all patients) have needs surrounding disposition planning, scheduling, patient education, and care coordination with other providers spanning services beyond the surgical care episode.

Telemedicine offers tremendous efficiencies compared with the face-to-face health care delivery model, but these efficiencies are lost when critical institutional support functions are cut in the process of streamlining. An institutional commitment to telehealth care delivery must include care team-building through consistent staffing and ongoing training. Resources such as quick-start guides and implementation tool kits can be used to initiate or expand telehealth services, but a long-term commitment from institutional leadership is essential to effect culture change.4,11,12 Surgeon champions can be a critical force for care transformation to include telehealth as a part of our standard surgery care delivery.

As the advocate for surgeons and surgical patients, the ACS should lead the way in promoting responsible policy and supporting the use of standards of practice for surgical telemedicine. The ACS should work to define the gold standard or best practices for a virtual surgical examination. Culture change is an issue with telemedicine; the virtual examination relies much more on listening and visualization. This change is analogous to the adoption of laparoscopic surgery, where our hands were removed from direct patient contact during the operation. Surrogates for the hands-on examination include a remote examiner or use of bio-peripherals, and the ACS should advocate for best-practice integration of these enhancements to the clinical encounter.

The ACS also can support grassroots advocacy issues, especially in key areas, such as originating site definition, cross-state licensing, new remote monitoring codes, and payment parity. Finally, the ACS should join the American Telemedicine Association and other surgical organizations, such as the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons, to advance adoption of surgical telehealth, advocate for government and market normalization, and provide education and resources to help integrate virtual care into emerging value-based delivery models.

*All specific references to CPT codes and descriptions are © 2020 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. CPT is a registered trademark of the American Medical Association.

References

- Society of American Gastrointestinal Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES). Guidelines for the surgical practice of telemedicine. Surg Endosc. 2000;14(10):975-979.

- Harkey K, Kaiser N, Zhao J, et al. Postdischarge virtual visits for low-risk surgeries: A randomized noninferiority clinical trial. JAMA Surg. January 13, 2021 [Epub ahead of print].

- Scott Kruse C, Karem P, Shifflett K, Vegi L, Ravi K, Brooks M. Evaluating barriers to adopting telemedicine worldwide: A systematic review. J Telemed Telecare. 2018;24(1):4-12.

- American Medical Association. Telehealth Implementation Playbook. 2020. Available at: www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2020-04/ama-telehealth-implementation-playbook.pdf. Accessed February 18, 2021.

- U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration. Billing for telehealth during COVID-19. Available at: https://telehealth.hhs.gov/providers/billing-and-reimbursement/. Accessed February 18, 2021.

- Mullangi S, Agrawal M, Schulman K. The COVID-19 pandemic—an opportune time to update medical licensing. JAMA Intern Med. January 13, 2021 [Epub ahead of print].

- Aalami O, Ingraham A, Arya S. Applications of mobile health technology in surgical innovation. JAMA Surg. February 3, 2021 [Epub ahead of print].

- Gunter RL, Chouinard S, Fernandes-Taylor S, et al. Current use of telemedicine for post-discharge surgical care: A systematic review. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;222(5):915-927.

- Asiri A, AlBishi S, AlMadani W, ElMetwally A, Househ M. The use of telemedicine in surgical care: A systematic review. Acta Inform Medica. 2018;26(3):201-206.

- Nandra K, Koenig G, DelMastro A, Mishler EA, Hollander JE, Yeo CJ. Telehealth provides a comprehensive approach to the surgical patient. Am J Surg. 2019;218(3):476-479.

- Smith WR, Atala AJ, Terlecki RP, Kelly EE, Matthews CA. Implementation guide for rapid integration of an outpatient telemedicine program during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Surg. 2020;231(2):216-222.e2.

- American College of Surgeons. ACS COVID-19 telehealth resources. Available at: www.facs.org/covid-19/legislative-regulatory/telehealth. Accessed December 13, 2020.