From Ancient Greece to the 20th Century

Xenotransplantation, from the Greek “xénos” (foreign, guest, strange), refers to the transplantation of tissues across species barriers. The first successful clinical xenotransplant in ancient legend was performed by Daedalus, who grafted bird feathers onto his arms to escape by flight from Crete to Athens. The first xenograft failure was noted in Daedalus’s son Icarus, who developed hyperacute graft rejection due to a thermolabile reaction.1

Later attempts at clinical xenotransplantation began in the early 20th century, when advances in the understanding of physiology led to new interest in renal xenografts. In 1906, Mathieu Jaboulay, a professor of clinical surgery in Lyon, France, attempted two heterotopic renal xenografts from a sheep and goat; both grafts failed due to hyperacute rejection with vascular thrombosis.

In 1910, Ernst Unger, a German physician and surgeon, performed a renal xenotransplant from a nonhuman primate to human, which similarly failed after 32 hours due to vascular thrombosis.1 In 1923, Harold Neuhof, a pioneer of thoracic surgery, performed a renal sheep-to-human xenotransplant at Mt. Sinai Hospital in New York City. This xenograft survived for 9 days and represented a leap forward in xenograft survival.

Dr. Neuhof later wrote: “[This case] proves, however, that a heterografted kidney in a human being does not necessarily become gangrenous and the procedure is, therefore, not necessarily a dangerous one, as had been supposed. It also demonstrates that thrombosis or hemorrhage at the anastomosis is not inevitable. I believe that this case report should turn attention anew.”2 Dr. Neuhof was a founding member of the American Board of Surgery in 1937.

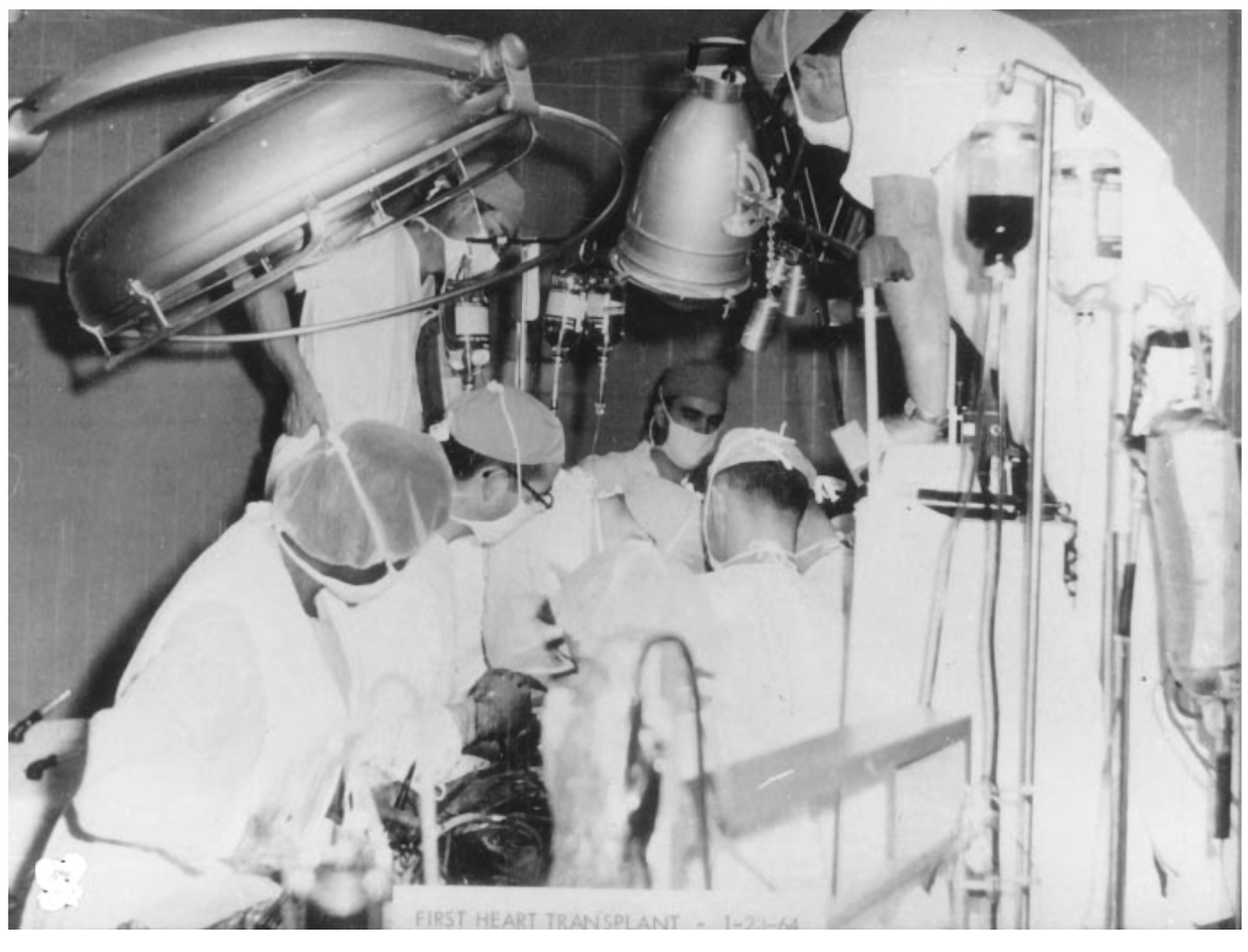

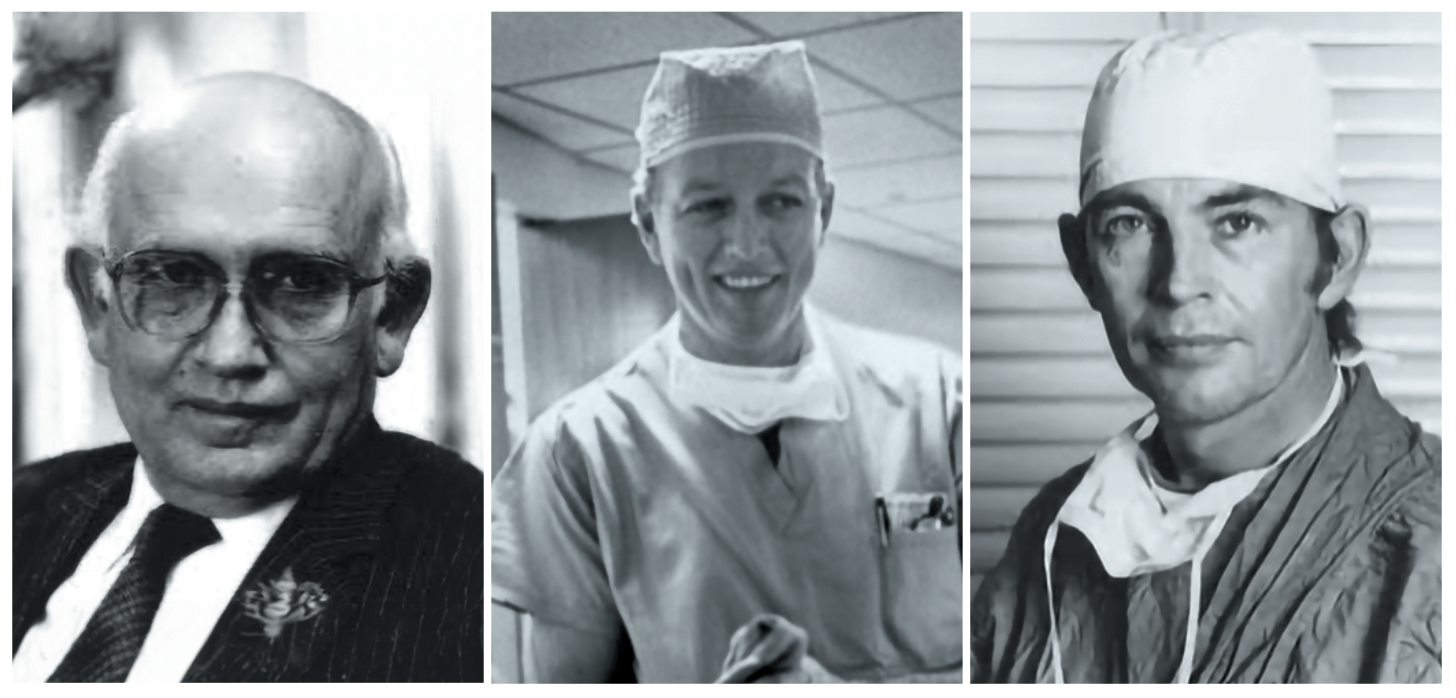

The next attempts at renal xenotransplantation followed the development of renal replacement therapy by hemodialysis in the 1940s and 50s. While hemodialysis treatment showed exciting promise at sustaining life, the relative shortage of dialysis machines led to new innovations in renal replacement. In 1964, Keith Reemtsma, MD, a surgeon at Tulane University in New Orleans, Louisiana, published reports of 13 chimpanzee-to-human xenotransplants. While most grafts survived 4-to-6 weeks, one of these xenografts survived for more than 9 months and allowed its recipient to return to activities of daily life, including work as a schoolteacher.3

Also in 1964, Thomas E. Starzl, MD, PhD, FACS, published a report of six baboon-to-human renal xenotransplants with varying success, as well as heterotopic auxiliary liver xenografts.4,5 Dr. Starzl would pioneer human liver transplantation in 1967, and later the use of cyclosporine and tacrolimus.